|

Challenges with Inventory Management in the Caribbean

Distribution firms in Caribbean countries range in size up to $150M USD in annual revenues. Their geographical position means that they handle multiple challenges in their supply chains to service local markets, including:

- Supply chain uncertainties from worldwide sourcing, such as long lead times, lead time variability, and supplier yield. Yield is twofold issue; it represents both supplier fill rate against ordered quantities, as well as the level of products supplied conforming to specifications.

- Currency movements in source and local markets, which impacts costs, prices and demand.

- Natural disasters, most notably hurricanes.

In addition to these factors, the relatively small size of customers, the low levels of industry consolidation, and comparatively poorly developed material handling infrastructure means that distribution firms have to overcome the challenges of losing unit load efficiencies in distribution, which drives operating expenses higher.

Caribbean distribution companies have not been immune to the general downturn in consumer markets over the last year, and they face serious cost and service level challenges. One area that presents significant opportunity to firms is to reduce their inventory levels and their associated inventory costs. For the purposes of this article, the grocery industry serves as a good example of the common issues that are faced in the Caribbean.

The Domestic Grocery Industry Channel Structure

Product Ranges

Distributors sell locally manufactured and overseas manufactured products, under distributor agreements, in addition to their own branded products. Local and overseas manufactured products are sometimes distributed under competitive distribution arrangements, when the manufacturer believes it would improve market coverage. Under these arrangements, many distributors will sell identical SKUs to retailers as part of their portfolio.

Firms Making Up the Industry

Consumers shop at supermarkets, large wholesalers and small shops. The supermarkets and large wholesalers represent the first and main tiers that distributors service. The smaller shops generally purchase directly from larger wholesalers, although some distributors have begun to develop van sales operations to service smaller shops to achieve greater market penetration.

The industry is fragmented both from the distribution and retail sides, with little cooperation amongst the players:

- Many distributors provide competing products to retailers. It is not unusual for a large retailer to have a list of over 300 vendors/distributors. There are no initiatives to consolidate product distribution so that the retailer will see fewer vendor trucks.

- Store chains have been growing, but retail ownership is still generally family based, with no individual group dominating the retail trade. It is not unusual for a large grocery distributor to service over 1500 large and small accounts. Larger retail chains have avoided investment into a centralized distribution infrastructure, such that distributors are required to service each retail store within a chain as direct store delivery from their centralized distribution facilities.

- Hotels and restaurants are a comparatively small element in the grocery sector, and are also serviced directly by food distributors.

Structural Consequences

The main implication of this structure is that the grocery industry in the Caribbean has higher than optimal costs. These costs arise from operating inefficiencies and high inventory levels throughout the system. Some of the sub-optimal practices include:

- Distributors aggressively push product to retailers using highly competitive deals. Essentially, distributors attempt to “block” each other’s sales efforts by encouraging retailers to fill their stockrooms with their product, so that no other distributor’s products will easily fit within the remaining space in the stock rooms. Distributors tend to stock high inventories to support these sales “pushes” to meet their budget targets. Interestingly, distributors will commit to many of these sales “pushes” at the last minute when they are too late to include them into their own procurement forecasts.

- There are no delivery schedules to customers, and this results in multiple vendor trucks waiting in queues at the customer’s receiving doors. A truck sometimes gains priority by a willingness of drivers and their assistants to “repack” the retailer’s storage area, to make space for incoming product. The material handling at retail stores is entirely manual, with goods transfer from the trucks to storage being done entirely by hand on an individual case by case basis. As a result, transportation assets are tied up for long and unpredictable periods of time, which means higher overall transport costs for each distributor. There is also no guarantee that a truck will be unloaded when it is in the queue, particularly if the retailer has to run into overtime to deal with the trucks. The drivers are simply told to return the next day. This system fosters inherently unreliable and inefficient retail replenishment, so higher buffer stocks need to be maintained by retailers. One aspect of distributor behavior that this has created is that the distributor sets its own time standards for deliveries. Typically distributors will attempt to ship orders out as quickly as possible, generally within 24 hours for nearby customer accounts, and 48 hours for those further away. The retailer, however, has no idea of exactly when the order will arrive.

- Pricing differences between distributors selling similar or the same SKUs can result in retailers returning shipments without penalty. This situation occurs when the retailer receives a better deal from another distributor and the first distributor is unable, unwilling, or slow to respond to a price matching. Distributors therefore strive for differentiation by maintaining a product portfolio which has high consumer acceptance (brand strength), so that the retailer will always want the delivery.

- The lack of consolidation among distributors and retailers means that inventories of identical SKUs are replicated at both the distributor’s distribution centers and the retailers’ storage rooms within each store, increasing overall system wide inventory and handling costs.

Against this background, there is a bit of an industry dilemma. Retailers want cost savings from reduced inventory holdings, but they require greater distributor reliability before they can cut their safety stocks. Distributors also want cost improvements in significant inventory investments, but they do not want to risk losing sales “push” opportunities with too low an inventory level.

Common Inventory Policies in Use by Distributors

One of the factors driving inventory levels is the strong desire from all participants (vendors, distributors and retailers) to have good stock availability to support sales. In spite of these efforts, common “good” service fill rates are only between 85 and 92%. Inventory levels at distributors are driven by a variety of policies:

- Overseas manufacturers that have strong international brands typically set annual volume targets, broken down by month, that the distributor is required to receive. The manufacturer meets budget based on total shipments, but the distributor meets budget based on sales to retailers. Having had this volume pushed at it, the distributor in turn pushes this volume through to retailers. Any slowdowns in retail caused by consumer behavior are generally offset through volume deals, and consumer promotions funded by the overseas brand owner. The stocking levels required by overseas brand owners are typically between the extremes of 6 and 12 weeks of sales. These stocking level requirements are often the subject of intense negotiation because of the increased inventory costs that the distributor has to bear.

- “Rules of Thumb” are often used, an example being 8 weeks of stock for A items. These rules are largely developed based on experience and are neither regularly challenged nor reviewed. For some products harvesting/processing (e.g. for some types of fish), occurs only once annually, so that annual requirements have to be decided in advance of the season.

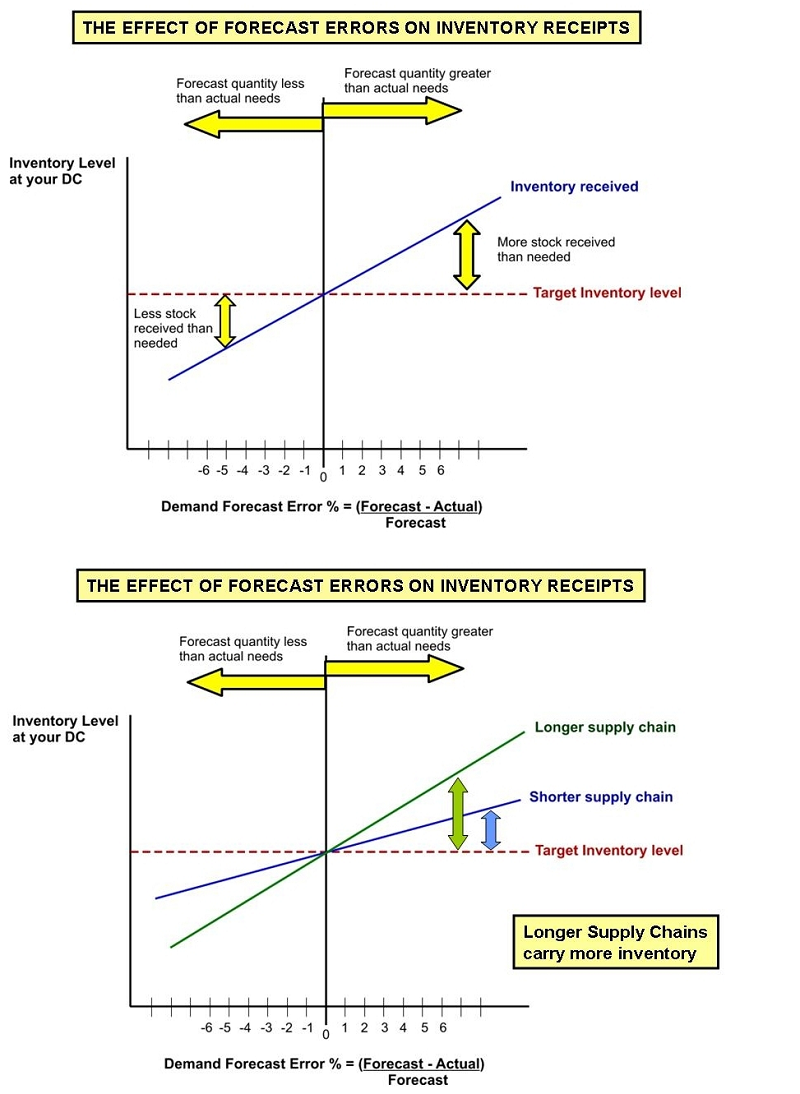

- As surprising as it may seem, there are distributors that have no explicit rules or formulas. Replenishment orders are made to suppliers on the basis of demand forecasts for the coming months. In most instances, forecasts at the SKU level are not very accurate, and this results in inventory inflows from suppliers that do not match actual demand - creating either “feast” or “famine” inventory situations. Buyers in these firms spend an inordinate amount of time adjusting orders and expediting shipments to try to achieve adequate - but not excessive - stock levels. When there are forecast errors, the long lead times associated with some products increases the volatility of inventory swings.

Setting the Inventory Policy

Inventory policies need frequent review to create and maintain improvements to inventory levels and still support existing service levels. Holding higher than required stocks means that a distributor must tie up working capital in inventory and incur higher inventory carrying costs. Some of the areas that contribute to distributors not achieving “optimal” inventory levels in their supply chain include:

- Safety stock inventory is inventory carried over and above the required for normal “average” demand to cover anticipated variances that will occur. However, the levels of safety stock that need to be carried are frequently not explicitly defined. Some of the factors that contribute to this situation include:

- The use of traditional mathematical formulas (e.g. reorder point) to drive inventory purchases is notably lacking. In fact the inputs to these formulas are frequently statically setup and not tracked. These include:

- Lead Times

- Lead Time Variances

- Demand Variances

- Supplier performance from a yield perspective (conforming product fill rate versus order) is not tracked or used.

- Inventory variances are not incorporated in calculations. Controlling variances is often a significant challenge and these are often identified and booked only on the basis of official quarterly physical stock counts. The IT system is the “true” indicator of stock levels and is therefore not updated as these variances occur, and system inventory is therefore potentially incorrect by this factor.

- Anticipated declines in the local currency creates a “run” on distributor inventories by retailers, since they recognize that newer stocks will come in later at higher prices. Safety stock decisions do not include these anticipated changes.

- Risk assessments that suggest the need for increased safety stocks (e.g. in a projected active hurricane season), require the approach of different safety stock levels to be maintained for different seasons.

- Policy stock levels, and the associated safety stock levels do not undergo frequent reviews as situations change, such as improved lead times, or improved lead time variances.

- Distributors try to optimize their own stock levels without trying for a wider view of controlling inventory levels in conjunction with the trading partners in their supply chain. This “local optimization” leaves inventory at levels that could be further reduced in the overall supply chain.

- No distributor exclusively supplies the full SKU range that retailers require, and there are no efforts to create this arrangement. Inventory is duplicated among distributors. This leaves inventory at levels that could be further reduced in the supply chain.

- There are few efforts to reduce lead times, components of variability or forecast error, which increases both the normal inventory and safety stock levels required.

- There are few efforts to optimize the distribution networks to minimize the sum total of purchasing, transportation and inventory costs.

Marc Wulfraat is the President of MWPVL International Inc. He can be reached at +(1) (514) 482-3572 x 100 or by clicking here. MWPVL International provides supply chain, logistics distribution consulting services including purchasing and inventory management. Our services include: distribution network strategy; distribution center design; material handling and automation design; supply chain technology consulting; product sourcing; 3PL Outsourcing; and purchasing; transportation consulting; and operational assessments.

|